Spirit of the Fight: Swordsmanship and Its Artful Practitioners

Pride of the Aristocracy, Soul of the Samurai – Collections including swords of Regents and Shoguns.

Till March 31st at Kasugataisha Museum

A superb exhibition of swords at Kasugataisha Museum comes to a close at the end of this month. Japan can always be relied upon to throw a good show, large or small, since its repositories of premodern art and historical artifacts are often ones – temples and shrines – that are full of exceptionally high quality offerings to the gods, or objects that were created as icons. They therefore demand treatment as actively sacred objects that (arguably) require expenditure of greater preservation efforts than those deemed absent of holy alliance or meaning do. Whether preservation is indeed superior or just different is a question worth exploring – though this isn’t the place to do that. But admirers of sword manufacture, swordsmanship, decorative art, as well as historically situated ideologies of warfare, and those interested in how weapons crossover into the worlds of highly refined dance costume and choreography and of social status signified by apparel, will find rich pickings at Kasugataisha’s exhibition.

As is often the case with museum and art exhibitions in Japan, English (not to mention other foreign languages) information is rather scarce, but that should not dissuade the enthusiast or the curious. To a certain extent the pieces on display speak for themselves. They range in age – the exhibits date from the 12th to the 19th century – and in type, from long and short, shakudozukuri and hyogogusari types, and some small koshigatana hip-swords. The smiths and donors of several are attested – the former mainly of Echizen and Bizen provinces, both famed for their swordsmiths, the latter include the Fujiwara regency and Ashikaga shogunal clans. Materials used in the hilts and scabbards are of a rich variety: black and red lacquer is common, but brocade is sometimes used, as is mother of pearl inlay, along with rock crystal and semi-precious stones, stingray rayskin (called “sharkskin”), and silverplate.

Though the swords on display are largely ones offered to the deities of the shrine, viewers might be reminded of not only how rare the possession and acquisition of skill in handling swords were but also how meaningful possession and skill was. Swords were generally considered not merely objects, but inhabited by souls or spirits, and so they possessed an identity for their owner that went beyond that associated with function as weapon, personal belonging, or symbol of status/authority. They were additionally embedded in a much wider culture of meaning: particular battles (and a history, cultural memory and ideology of battles) and warcraft; a now extinct hierarchy of power; a world of other objects imbued with spirits; and a world in which the body of a fighter operated in distinct ways. Brutal though he may have been in practice (as illustrated by some gory scenes in the 18th century Kasuga Gongen Genkie picture scroll) the sword-wielding warrior moved according to a certain choreography. The phenomenon of subsuming violence and killing into an elegant, luxurious part of a nobleman’s apparel (and, in the 17th and 18th centuries, its non-functional inclusion in the wear of the non-fighting samurai class) is also something to keep in mind. In part, this subsumption reflects societal attitudes toward fighting and battleground death – swordsmanship has cross-culturally often been an art as much as a method of destruction – something nicely encapsulated in the title of the exhibition. The same collusion of meaning and function smoothed into dignified art is found in traditional dance: a lot of fighting moves and scenes are used in courtly Bugaku.

A sword that is part of a Bugaku costume for the “Taiheiraku” dance and dated to between the 17th and 19th centuries is on show. It has an attractive white sharkskin hilt, inlaid rock crystal, and some exquisite bronze metalwork of curling vines leave and flowers. The shark (ray) skin, what looks like a sheath of tiny, twinkly white beads, was imported from the India, Thailand or Indonesia. It was a luxury material but also quite durable and provided a good grip. Other pieces are similarly ornamental and had been forged and decorated specifically as offerings to the deity of the Kasuga Grand Shrine by patrons and members of the clan who worshipped this deity as their clan god.

In 1135, the Fujiwara regent Tadazane and his son Yorinaga offered a rosewood sword to a newly-introduced young Wakamiya deity. Its mother-of-pearl inlay and black lacquer motifs of birds, trees, and mountains over silver plate are a one of a kind technique called Kinban kurourushi densō. It is a uniquely beautiful work of art and craftsmanship. Yorinaga would have been 15 years old at the time. He died in the Hogen Insurrection just 21 years later, the battle that decisively ended Fujiwara dominance and marked the real start of the rise of samurai. The intensity of the often violent power struggles between factions throughout the feudal age is another background against which to understand these sword offerings – as symbols of power sought and requested from a higher power, in that power was as much a sign of plenty as the riches that adorned these swords were.

Please see the April 2024 exhibition listings for current and upcoming sword shows at The Museum, Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Prefecture, and Kashihara Shrine Treasure Museum.

Silent Dust Swept Away: Kūkai at NNM

Kūkai: The Worlds of Mandalas and the Transcultural Origins of Esoteric Buddhism at Nara National Museum, Sat, Apr 13, 2024〜Sun, Jun 9, 2024 (Preview)

One of the exhibits in the upcoming Kūkai: The Worlds of Mandalas and the Transcultural Origins of Esoteric Buddhism that stands out for its novelty – and for what it suggests about the historical trajectory of esoteric Buddhism and its icons – is the 10th century seated bronze image of Mahāvairocana Buddha, a component of the “Sculptural Mandala of the Diamond World” excavated from the Mahapajit Temple Site in Nganjuk, Java. The broad geographical network that shaped esoteric Buddhism both before and after it was adopted in Japan included Indonesia, an area that is rarely acknowledged in exhibitions of esoteric Buddhist art here. Indeed, there are significant developments in the meaning and portrayal of Mahāvairocana the principle deity, and the wrathful deities that had entered Java before esoteric Buddhism had been fully adopted in Japan (known there as Mikkyo), so exposure to iconography there may be helpful in piecing together the story of Buddhism across the region (and how it contrasts doctrinally and iconographically from its counterparts in other cultures), and the equally compelling stories of the deities, their battles, and their places in the cosmos. Indeed this transculturalism is indicated by the title of the exhibition – and the promised exploration of it is one of the main attractions. Sculptural representations of the mandalas are relatively rare, and this one, though much smaller, might be compared with an early three-dimensional mandala in Tōji Temple, Kyoto, as well as with the much more common painted mandalas. A link between the Nganjuk mandala and the Diamond World mandala of the Shingon school of Japanese esoteric Buddhism has been suggested by Seno Joko Suyono here.

National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta

Indonesia, 10th century

A second object of note is the Takao Mandala, which is being shown for the first time after a six-year conservation that began in 2016.

Takao Mandara: Diamond World

Jingōji Temple, Kyoto

Heian period, 9th century

The “Ruler of the Silent Dust”, the name bequeathed upon Siva in a transformation by a triumphant Vairocana, an episode that explains some of the imagery of the Nganjuk mandala and a notable one in the story of esoteric Buddhism as Hindu and Buddhist beliefs in India came into contact and conflict with each other, operates as a nice (if twee?) metaphorical image for the exhibition as a whole – though artifacts excavated are silent (and dusty) no more, and the Takao Mandala is likewise restored and renewed. As they move through cultures, deities’ names and their images transform through contact, conflict, resolution, absorption. The Nganjak Vairocana in conjunction with its Japanese counterpart, Dainichi Nyorai is a reminder of this: the mythical creatures surrounding his mount – the piscine makara, and the horned wyālaka lions – are Indian, and never made their way to the sparer depictions of this deity in Japanese esoteric Buddhism.

Nara National Museum’s show promises to be a superb one, in part because Japan’s collections of Mikkyo art are rich and well-preserved. But it also stands out among the steady stream of such shows in Japan that have been put on over the last few years (in approximate correspondence to the 1250th anniversary of the birth of the founder of this school of Buddhism in Japan, Kūkai (774-835)) because brand new exhibits are unusual, so the concept and content of this early-summer show is particularly welcome. Another piece on display, on loan from Beilin Museum, Xi’an merits mention here: an 8th century Wenshu (Skt. Mañjusri), excavated from the Anguosi Temple Site in Xi’an, which is a fine sculpture (and a Class One National Treasure in China). The curators of the Nara National Museum show speculate that this may have been seen by Kūkai while he was in that part of China, and – whether he viewed this particular statue or not – it offers extra context to the trans-Asian background and intermingling of Buddhist traditions that may or may not have influenced its iteration in Japan. (Another preoccupation found in scholarship is what, exactly, Kūkai was exposed to and possibly influenced by during his sojourn – in this vein, some wild theories have whirled around the so-called Nestorian Stone in Xi’an. Writer Shiba Ryotaro’s colourful vision of Xi’an at the time of Kūkai’s life there, which really was a metropolis populated and passed through by people of a wide array of ethnicities, occupations, and religions, is brought to life in his transporting (and sometimes imaginative) history, Kukai the Universal.) But differences – most obviously in styles – evidenced by this Wenshu statue can jolt the viewer out of an over-familiar and fossified view of Buddhist art, and Mikkyo, in Japan. It’s also fantastic as always to see museums of Buddhist art in Japan collaborating with museums in other parts of the Buddhist world – here, the National Museum of Indonesia and the Beilin Museum in China.

Excavated from Anguosi Temple Site, Xi’an

Beilin Museum, Xi’an, China

China, Tang dynasty, 8th century

Within the broader theme of transculturalism, the show focuses on founder Kūkai, his own vision of Mikkyo, and items associated with him. Some years ago, art historian Cynthea Bogel published a highly detailed and thoughtful book on the subject Kukai encapsulated in his statement “With a single glance [at the representations of the mandala divinities] one becomes a Buddha” – which provides the name of the book (With a Single Glance: Buddhist Icons and Early Mikkyo Vision). Here, Kūkai gave preeminence to the function of images over text when it came to grasping the teachings of Mikkyo. He was explicitly referring to the use of mandalas which though a somewhat contested question among present-day scholars of Mikkyo art and ritual is largely understood to be the internalization of deities. The 9th century Takao Mandala (more accurately, mandalas) is a pair of paintings which express the “Two Worlds” of the cosmos as understood by Mikkyo adherents. They are said to have been made by Kūkai based on mandalas he had brought back with him from China, and are the oldest of the type in Japan. The depiction of the cosmos of deities is delicate, decorative, and fairly simple – strictly diagrammatic delineations in gold and silver on a dark background – and because of the paintings’ age, origin in Kūkai, and status they invited reverence and interest over the centuries and were rather frequently moved around, and also repaired several times at the behest of emperors. They are certainly worthy of close examination and appreciation. Other items owned (or believed to have been owned) by Kūkai include a set of ritual tools, an initiation record, and a letter to fellow priest Saicho with whom he had a difficult relationship because of conflicting views regarding the correct transmission of the esoteric teachings.

A good selection of genres will be on display: paintings, picture scrolls, statues, ritual implements, and texts. The exhibits include around 30 designated National Treasures – one of which is the oldest set of Five Wisdom Buddha statues in Japan – and 60 Important Cultural Properties.

Sat, Apr 13, 2024〜Sun, Jun 9, 2024

Special Exhibition

Celebrating the 1,250th Anniversary of Priest Kūkai’s Birth: KŪKAI The Worlds of Mandalas and the Transcultural Origins of Esoteric Buddhism

9:30 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

(Last admission at 4:30 p.m.)

Closed on Mondays except Apr 29 (National Holiday) & May 6 (Substitute Holiday). Closed on May 7th.

Nara National Museum

East Wing and West Wing

50 Noborioji-cho, Nara

Admission

Adults: 2,000 yen

University/High School Students 1,500 yen

Admission free for junior high school students and younger

Talks & Events

All talks take place on Saturday afternoons from 1:30-3pm in the Lecture Hall of Nara National Museum. Admission is free but prior registration is required. Please see here for registration. All events are in Japanese.

April 27th (Saturday) 「空海マンダラの世界―宇宙へのいざない」Kukai and the World of Mandalas: an invitation to the universe

Matsunaga Junkei (Vice President of Koyasan University)

Tickets available April 1st (10am) – 15th (5pm)

May 18th(Saturday)「日本仏教史における空海と密教」Kukai and Mikkyo (Esoteric Buddhism) in the History of Buddhism in Japan

Saiki Ryoko (Director of the Artifacts Office, Curatorial Department, Nara National Museum)

Tickets available April 22nd (10am) – May 6th 5pm

25th May (Saturday) 「高雄曼茶羅ー弘法大師御筆の両界曼荼羅」The Takao Mandala: The Mandala of the Two Worlds Drawn by Kobo Daishi [Kukai]

Taniguchi Kosei, (Director, Planning Office, Curatorial Department, Nara National Museum)

April 30th 10am – May 13th 5pm

Special Event:

May 25th (Sunday) 1:30-3:30 (10 minutes per performance)

In one of the exhibition rooms at the museum, students of Shuchi-in University (an esoteric Buddhist university) will perform Shomyo, the melodic and rhythmic chanting of sutras.

Art, Buddhism, Buddhist art, Buddhist icons, Esoteric Buddhism, Esoteric Buddhist Art, Japan, Japanese Art, Museums, Nara, Nara National Museum, religion, Shingon, travel

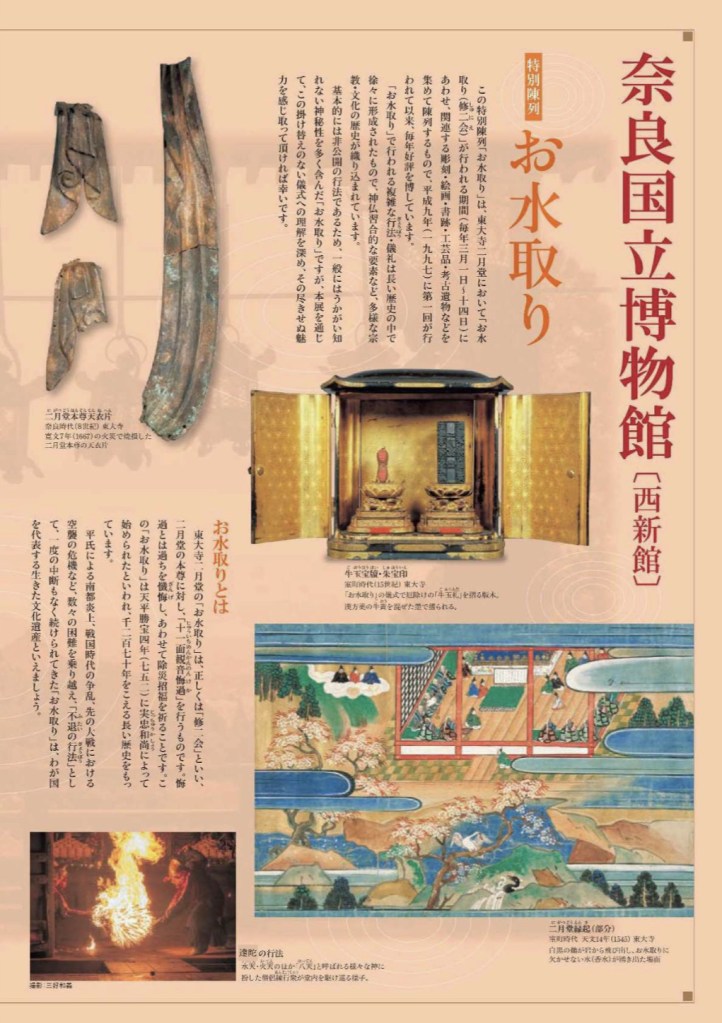

Tōdaiji’s Omizutori: Mystery and Otherness Restored

Todaiji Temple’s Omizutori Ritual – & Omizutori Museum Exhibitions in Nara

Religious practice in Japan is sometimes tamed by way of museum exhibitions and by the contemporary secular viewer of such exhibitions, making it, whether consciously or not, “mere ritual”: performance art or piece of theatre, political expression, or display of eccentric quirky superstition. It may be any or all of these things, but the subsumption often reflects materialism or a lack of belief that is projected onto the performance of the ritual itself and assumed of its participants. When this happens, we don’t give credit to the way that the spiritual world pervaded premodern Japan, and arguably still does today, whether that is ritualistically acknowledged or not. Current exhibitions focusing on one particular ritual at Nara National Museum (Treasures of Todaiji’s Omizutori Ritual) and at Todaiji Museum (Nigatsudo: The Ritual Space of Todaiji Temple’s Shunie Repentence Ceremony) explain but also restore some of the mystery and otherness – fearful, reverent, and sometimes downright puzzling – of the spiritual dimension and the way that people interact and negotiate with it, delivering quite a special experience to their visitors.

The Omizutori (“The Sacred Drawing of Water”) is one of the major and more impressive rituals of Todaiji, Nara’s most famous and most-visited temple, which – with its imperial connections – is quite literally majestic. Todaiji holds many claims to greatness. Architecturally, its principle worship hall is one of the largest wooden structures in the world; historically, it is one of the oldest Buddhist temples in Japan; and artistically, it houses an imposing 15 metre high “Great Buddha” statue that has long represented, like the temple itself, the power and influence of Buddhism in Japanese history. But one way to experience Todaiji as a present and living place of elaborate and deeply-felt devotion is the Omizutori, which takes place at its Nigatsudo Hall. And while many of the temple buildings and the Great Buddha itself have been reconstructed after instances of destruction, this ritual is an example of authentic longevity: it has been practiced every single year without a break since its founding in 752.

The Omizutori is made up of a series of rituals over the first two weeks of March. If you visit the Nigatsudo at sunset on any evening between March 1st and 14th you can observe one of them, a ritual called Otaimatsu (“Pine Torches”). Here, eighteen-foot long torches are carried by priests up to the balcony and vigorously swung around, and for around twenty minutes – via the sparks of fire, fragments of burnt torch, and embers that are showered down onto a gathered crowd – blessings of protection are bestowed for the coming year. The fiery spectacle is at its height on the last day of the ceremonials when the largest number of torches (eleven) is brandished by the priests producing a blaze that, from the balcony of a building made of wood, seems almost incomprehensible. The effect is one of awe, not only because the unfurling waves of flame are thrillingly beautiful, but because the wildness is controlled – after all, this has been practiced for centuries.

Nocturnal rituals that take place on March 12th and 13th between 1:30-3:30am similarly display the energetic and theatrical manipulation of water and fire, which used together constitute a highly purifying ascetic practice. On March 12th the priests ceremonially and repeatedly draw sacred water from a well to the sounds of blown conch shells, the rite which gives the whole ritual its name: Omizutori. The Dattan no Myoho (“Wondrous Rite of Fire Ascetics”), following this, is dance-like and performed by two priests, one bearing a bowl of sacred water and acting as the water god, and the other who acts as the fire god holding a gigantic, blazing torch. During these procedures six other monks who embody other gods appear one after another, rotating swords and staffs and flinging materials around.

Many aspects of the ritual seem incomprehensible, and the exhibitions at Nara National Museum and Todaiji Museum do a good job of explaining them without stripping them of their mystique. Its original name was “The Eleven-headed Kannon Ceremony of Repentance” since monks could repent of their transgressions through the power of the multiheaded Kannon bodhisattva enshrined in the Nigatsudo. The emphasis on purification by fire, water, and other means can be partially explained by the original and fundamental nature of the ritual.

Exhibits provide clues to the meaning of other aspects of the ritual. Founder monk Jitchu had invoked Kannon as a “living” icon, after having seen a vision of the ritual being performed by heavenly beings and deciding to imitate it. Kannon was thus drawn from its mythical residence Potalaka, washing up materially in a river, as depicted in the 1545 Karmic Origins of the Nigatsudo picture scroll displayed at Nara National Museum. Divine instructions received by Jitchu account for the startling performance of monks running and prostrating in the hashiri circumambulation section of the ritual. Not only did his iteration have to be in front of a “living Kannon” but it had to be performed 1000 times a day to be commensurable with its divine prototype. Jitchu’s solution was to perform austerities at the speed-of-running. As for the enshrined Kannon, to whom all this is offered, the icons (there are two) are completely concealed, even in images of the ritual found in the Karmic Origins. However, the appearance of one is divulged in a displayed picture scroll, a monastic collection of “Classified Secret Notes” from the early thirteenth century. It is a standing figure holding a vase and a rosary, with a plume of stacked up heads emerging from its crown. A replica of the shrine and part of the altar for this “small Kannon” is one of the exhibits at Nara National Museum.

Water, along with incense and light (lamps) is an essential offering to Buddhas and bodhisattvas. As legend has it, one local god of all those invited by Jitchu to the rite, Anyu Myojin, was late to the ritual and by way of apology offered scented water. This is why the monks ceremonially draw it from the Nigatsudo well, at which is is believed to have been divinely provided, and offer it to Kannon.

Some beautiful paintings depicting the temple grounds and buildings in which the events take place are also on view and are as valuable for their artistic quality as for the historical information they have preserved.

While this is a Buddhist ritual, some disparate influences are apparent, namely exorcistic ones. One monk is designated “Shushi” (Incantation Master) and his role mainly concerns dispelling bad influences and summoning helpful ones. Goblins, too, are ceremonially invited along for the events. A 17th century scroll of his words of purification (Onakatomi no harae) is on display. Enchantments and spells like these pervade the rituals, all of which reflect the practices of Shinto-inflected esoteric Buddhism, and are evidenced by exhibits: a woodblock for the mass printing of the circular sonsho dharani amulet, pulled from the rubble of a 1667 fire; paper wands; a ritual handbell (probably an enchanted object) packed artistically in thick paper. During the ritual, the monks handprint “spells” (dharani) which they offer to Kannon bodhisattva. After completion of the final ritual, the Incantation Master marks the forehead of each monastic participant with one of the signs found on the seals for printing – that of a red jewel.

The sounds of chanting, clanging, calling, of bells being rung, wooden clogs stamped, and of ancient Japanese music float over the exhibition halls from an introductory video – something I’ve experienced at other exhibitions at Nara National Museum and which is an effective way of enhancing them. Here they evoke a sense of presence at the ritual itself, giving an otherworldly atmosphere that highlights its true strangeness. The exhibits do this too – among many others, the strange form of the paper wrapped bell, the patched up black robes of the serving monks, the “classified” revelation of the secret bodhisattva icon, the photo of “the calling of the goblins”. All are initially puzzling but, by virtue of that, signal authenticity and a distant (and obscure) history.

This exhibition and the smaller Todaiji Museum show, which displays a collection of diagrams and texts that clarify the spaces and buildings used in the Omizutori, along with more of the Karmic Origins picture scroll, restore a solemn mystery and even a rather fearsome nature to the serious acts performed here that are far from “mere ritual”. The value of rituals such as these which have continued without a break up to the present day is not only in their fidelity to ancient form and content or in the unchanging power they are believed to exert, but also in their capacity to transport observers into a rare state of mind open to be accessed once a year, every year.

Special Exhibitions:

Nara National Museum, New West Wing: Treasures of Todaiji’s Omizutori Ritual

February 10th – March 17th

Todaiji Museum: Nigatsudo: The Ritual Space of Todaiji Temple’s Shunie Repentence Ceremony (Website info only in Japanese) February 10th – March 18th

February 10th – March 18th